|

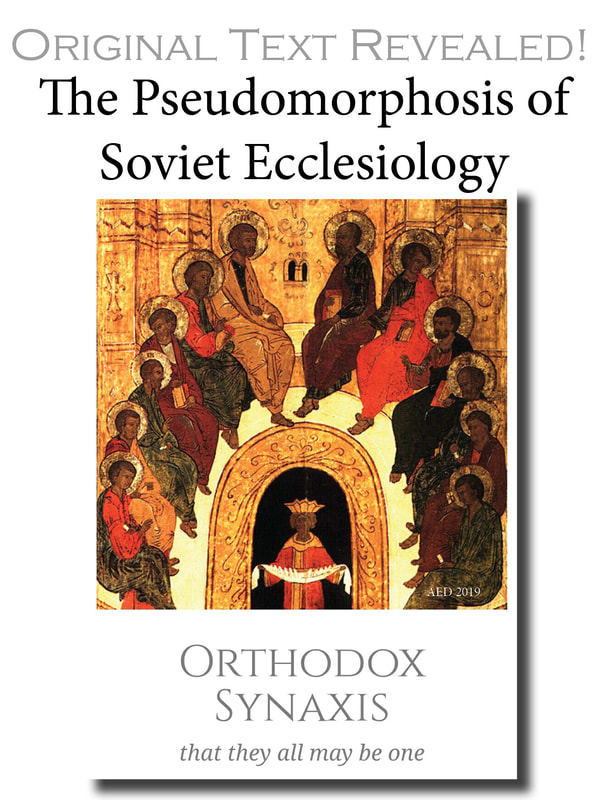

A Postmodern Literary Pastiche, Ecclesiological Pseudo Antonym, or Something Altogether Distinctive?

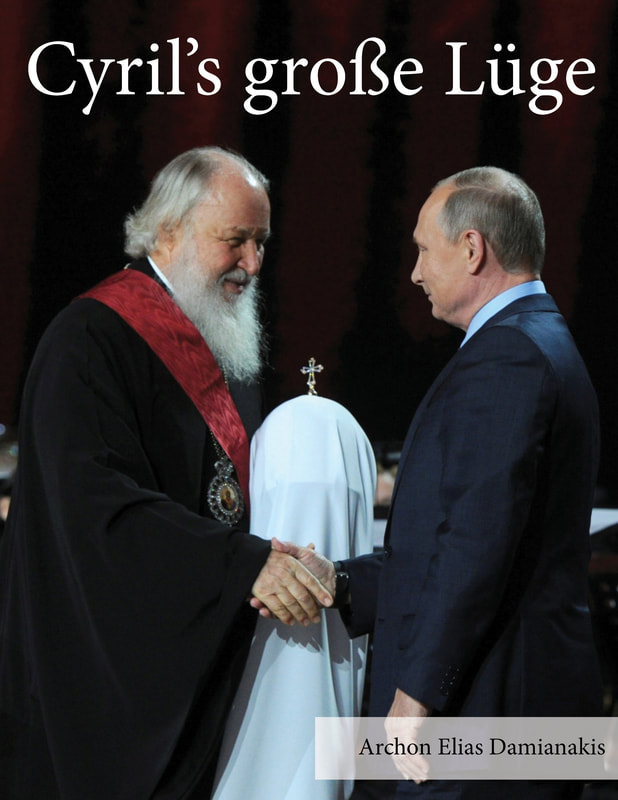

Recent assertions by the Moscow Patriarchate and communiques of Patriarch Kyrill to the “rest” of the Orthodox world are remarkably revealing documents, not only for their candid expression of the Patriarchate of Moscow’s ecclesiology, but also for the insight it gives into the patriarchate’s internal discourse and the historical touchstones of its self-understanding. It is striking that most of the examples and quotations cite to illustrate the Throne of Moscow’s desire for universally authority and dread responsibilities that transcend borders, which date from the Soviet period, to a degree that one might be tempted to suggest that the “Throne of Stalin” might be a more apt sobriquet. This period of the Church’s history, when the churches of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe were greatly weakened was, notwithstanding its own hardships and persecutions, a time of opportunity for the Moscow Patriarchate, when its proximity within the KGB allowed it to gain unprecedented authority over most of the other Slavic Orthodox churches. And it should be pointed out that in practice, the Soviet era began for the Moscow Patriarchate well before the end of WWII. Already in 1941, as Soviet armies swept through Eastern Europe, the Russian Orthodox Church was suppressed, and its territory given to the newly established Moscow Patriarchate by Joseph Stalin.

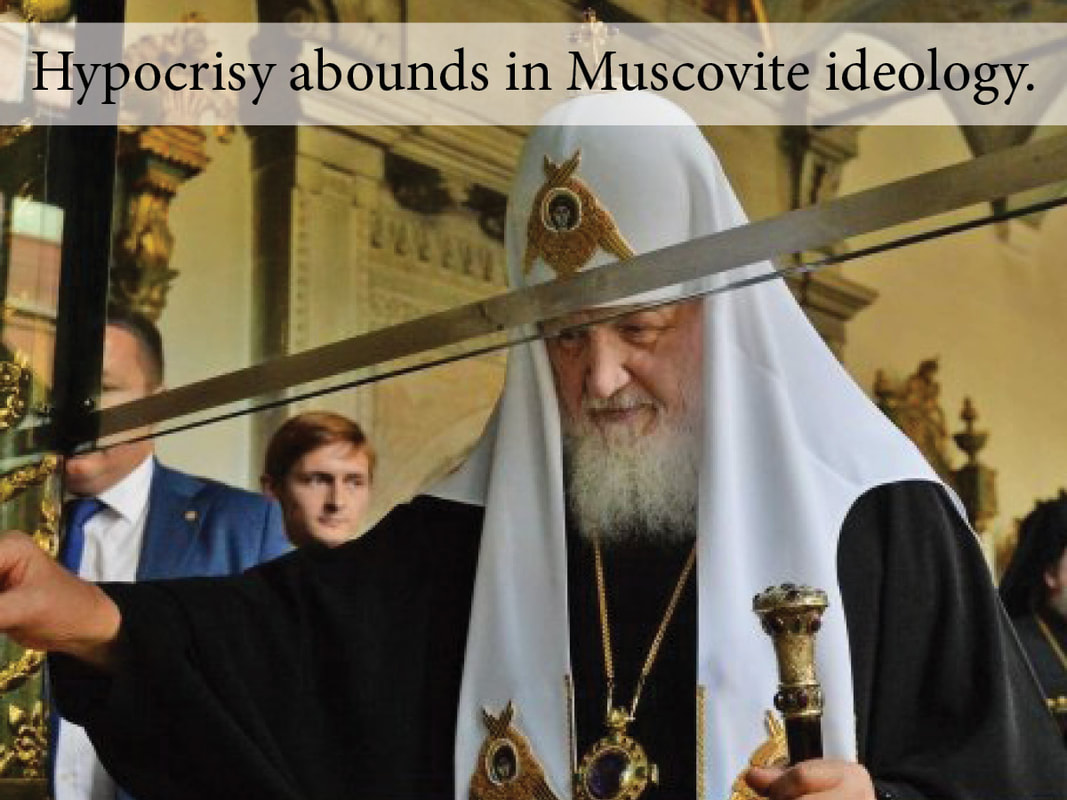

The unique circumstances of the Soviet period—severe restrictions placed on the exercise of normal ecclesiastical life coupled with Moscow’s unprecedented direct and indirect control over churches finding themselves in even more dire straits—led to what could be termed (borrowing from Fr Georges Florovsky’s description of the “Western captivity” of Russian theology) an ecclesiological “pseudomorphosis.” As Florovsky explains the concept, “Form shapes substance, and if an unsuitable form does not distort substance, it prevents its natural growth.” In the case of the ecclesiology, the unnatural form of church-state and inter-church relations distorted the substance of the Orthodox teaching and practice of primacy and conciliarity, where the role of the Moscow Patriarch and his curia of bishops residing in the capital was greatly exaggerated and the fundamental truth of the equality of all bishops and their conciliarity under one head, Jesus Christ, was forgotten. This can be seen in the heavily Soviet-inflected rhetoric of the Moscow Patriarchate today, where the ecclesiological pseudomorphosis lives on under the restrictive circumstances of modern Russia, as expressed by the Patriarchate’s desire to be seen as Pan-National Universal Church, exercising its “supervisory provision and protection” over the other churches and Russians anywhere in the world. The history of the Moscow Patriarchate under the Soviets was characterized by a bewildering institutional instability that currently belies Patriarch Kyrill’s claim that, in Moscow, “the only truly free Orthodox Church” we preach the genuine inheritance of ecclesiology because we draw from the wellspring of our Fathers and not from self-interest or other trivial motivations and political expediencies. In fact, it was precisely the “self-interest and trivial motivations” of Muscovite clergy that led to revocation of the Patriarchate in 1721 by Peter the Great. This is due to an institutional culture in which “intrigue, simony, and corruption dominated the higher administration of the Church” caused by the fact that every office in the church was permanently up for sale by the Czarist and later KGB authorities, who found eager buyers among ambitious and unscrupulous Russian clergy. It is risible that the Moscow Patriarchate, an institution whose offices were long the object of barter and whose bishops were notorious for treating their position as a business opportunity, could claim that it alone among the Orthodox churches has preserved an authentic ecclesiological consciousness. Of course, the Church of Moscow was not the only one to suffer under the Soviets and in the provinces the situation was often worse. Lacking the population of wealthy Christian merchants that existed in Moscow, churches elsewhere were reduced to penury and beset with their own destabilizing fractiousness. Patriarch Kyrill’s claims that Moscow’s interventions in other local churches were acts of “self-sacrifice” can only elicit a grimace of bitter irony from those familiar with the history of Orthodoxy in the former Soviet Union. The Patriarchate of Moscow effectively annexed the territories of the ever-expanding Russian empire. Throughout the region, the Patriarchate of Moscow, backed by the powerful Czarist merchant families who managed to establish their own dynasties of client-rulers, replaced local upper clergies with ethnic Rus who rarely had much in the way of spiritual concern for their flocks. This had no small role in fostering the ethnic and nationalist movements that gave shape to the modern “former Soviet Union”. The price paid by the Orthodox Church for its subjugation to its Soviet benefactors was heavy. First, it meant that the Church was run more and more in the interests of the KGB and not of Orthodoxy as a whole. The policy defeated its own ends. It caused so much resentment that when the time came neither the Serbs nor the Bulgarians would cooperate in any Russian-directed move towards homogeny; and even the Georgians held back. None of them had any wish to substitute Czarist for Soviet political rule, having experienced Russian religious rule. A similar process is happening in the Middle East. In Antioch, the Patriarchate of Moscow constantly used its position as the Soviet point-man to exploit the current crises. From the inception of Soviet influence in Syria the Moscow patriarch was established as the sole channel of communication between the Antiochian patriarchate and the Soviet central government and, subject only to the latter’s discretion, the final arbiter of its civil and ecclesiastical affairs. Had the enormous power wielded by the Moscow See as a department of the Soviet central administration been intelligently and decently employed in the summer of 2016. But, for reasons which cannot detain us here, the Muscovite Church in this period is not characterized by a particularly high degree of either integrity or stability. The Russian Church plays something resembling the role of well-paid but dishonest broker between contending factions in Antioch, Belgrade and Tbilisi. Much as in the former Soviet occupied territories, the chauvinism, corruption and mismanagement of Russian clergy proved to be a catalyst for the development of Orthodox nationalism. When the Holy Synod of the Living Church, Russians Exiled, or ROCOR finally surfaced, the Moscow Patriarchate did not respond in the loving and self-sacrificial manner that Patriarch Kyrill vaunts, but rather petulantly, refusing to add their names to the diptychs and suspending normal relations with them for decades. A petulant posture which Moscow implements often against the Body of Christ. It is evident in the Moscow Patriarchate the current ecclesiological crisis in Orthodoxy is also a conflict between incompatible collective memories. Where the Patriarchate of Moscow looks upon its Soviet past as the story of a mother selflessly and sacrificially caring for her children, both the churches subject to this care and most modern western historians view Moscow’s activity in this period as that of a corrupt and exploitative expansionist interloper. Thanks to pressure from the of the western powers, the Moscow Patriarchate managed to survive when its communist KGB coeval, the Soviet Union was abolished in 1991. Existing as it does today, this last surviving Soviet institution perpetuates a pseudomorphosis of ecclesiology that has prevented Orthodoxy unity from growing into an authentic expression of the Church’s life in the present, free from both nationalism and nostalgia for empire... “fear not isolation”

Nada Schleich Zec

4/1/2019 07:04:34 pm

La Paix au nom de Dieu entre les peuples frères ! Comments are closed.

|

Most Popular Posts

Archives

August 2024

Categories

All

Αγιογράφος

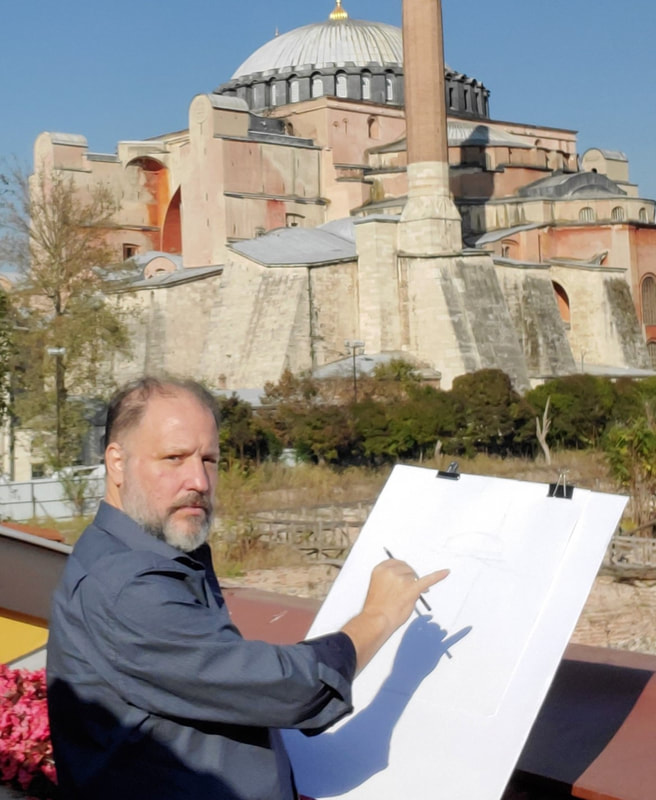

Ηλίας Δαμιανάκης Άρχων Μαΐστωρ της Μεγάλης του Χριστού Εκκλησίας AuthorBy the Grace of God Archon Elias Damianakis has ministered in the study of Holy Iconography since 1980. In his biography you can read about Elias' life and on his portfolio page you can see where he has rendered some of his hand painted iconography or visit the photo galleries to see some of his work. There is a complete list of featured articles, awards and testimonials which you can visit, as well as a list of notable achievements here below. Please contact Elias for more information or suggestions for this website, thank you and God Bless. |

||||||||

|

Orthodox Iconography

by the hand Sub-Deacon Elias Damianakis Hagiographos (Iconographer) Archon Maestor of The Great Church of Christ Archon of The Ecumenical Patriarchate [email protected] 727-372-0711 |

ο Άρχων Μαΐστωρ της Μεγάλης του Χριστού Εκκλησίας

Υποδιάκονος Ηλίας Δαμιανάκης -Αγιογράφος

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on this site are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any organization I have been, currently, or will be affiliated within the future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed